The year is 1933. Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) is President of the United States of America – it’s the first year of his first term and going on four years into the Great Depression. Unemployment is high and home ownership is plummeting; new buyers aren’t able to afford houses and people who had a home were defaulting on their loans. It was all around a bad time. President Roosevelt won the election largely based on promises to rejuvenate the economy, put Americans back to work, and lift struggling families out of poverty. His promise was a series of programs as part of a big New Deal.

In June of 1933, FDR signed into law the Home Owners’ Loan Act (HOLA) of 1933 (you can read more on that here) which established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). HOLC had the authority to issue bonds which could then be used to purchase loans in default to prevent foreclosures. (“The Corporation [HOLC] is authorized to issue bonds… which may be sold by the Corporation to obtain funds… to acquire… home mortgages and other obligations and liens secured by real estate… recorded or filed in the proper office or executed prior to the date of the enactment of this Act….”) This was a win for borrowers as their mortgages were refinanced at a lower interest rate as well as a win for the banks since they still got paid. However, this was not exactly a solution for the decline in new home ownership.

To address this continuing decline, the National Housing Act was passed the following year (you can read more on that here). With less money being put toward building housing, a major industry that was impacted by the Great Depression was the construction industry – the construction and manufacturing industries accounted for over sixty percent of total unemployment by 1937. The National Housing Act established two new federal agencies: The Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC) and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). The FSLIC and FHA, among other things, provided a level of insurance. The FSLC provided deposit insurance – a safety net for the people with money in the bank – while the FHA provided insurance to the lending institution; if a borrower defaulted on a loan, the FHA would pay on a claim to the financial institution. The proposal here was to improve access to mortgages for potential buyers by decreasing risk to the lenders, thus resulting in increased home ownership.

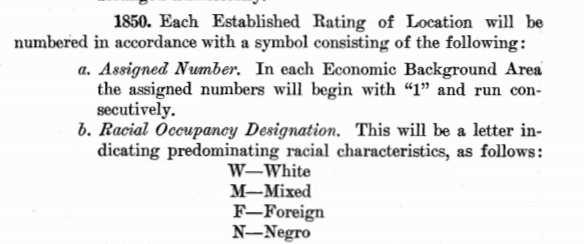

As lending is inherently risky, guidelines needed to be established to assess the risk of each loan and determine its eligibility for FHA insurance. Unfortunately, these guidelines were not strictly based on risk of the individual borrower. Some of the considerations, as outlined in the Federal Housing Administration Underwriting Manual, were Character, Family Life and Relationships, Associates, and Maturity – definitely things a stranger should be able to assess in an individual. This manual also contains a section regarding the “Compilation and Recordation of Data” (Part V, Section 18) that outlines the filing of FHA Form No. 2082 which includes a section for “Racial Occupancy Designation.”

The Racial Occupancy Designations were used in the “Established Rating of a Location,” which were composed of a neighborhood number followed by a letter indicating the primary racial makeup of the population and the property value range (the example in the manual is 28W-7-12-9 which notes that neighborhood 28 is primarily white with houses ranging from $7,000 to $12,000 with the most common price being $9000). The Established Rating was used “as a basis of comparison… with the rating of other locations in the same outlined neighborhood.”

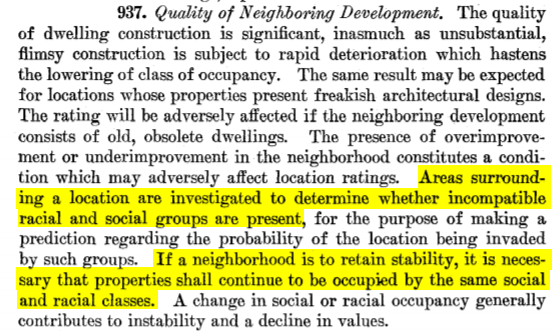

Separate from the Established Rating was the “Rating of a Location.” It was described as the process and resultant rating of “mortgage risk attributable to [a] location” with a primary purpose of determining “the degree of… risk involved because of the location of a property….” The basic principles of location rating defined “competitive locations” as “locations which are appropriate for residential structures having price ranges… typical in the immediate neighborhood.” However, it clarifies that similar price ranges do not “provide a basis for such comparisons if certain racial aspects render the locations actually noncompetitive.”

Each location was part of a neighborhood and, more importantly, an “Outlined Neighborhood.” Outlined Neighborhoods were “established for the purpose of indexing and classifying” these ratings and were “numbered on Outlined Neighborhood Maps.”

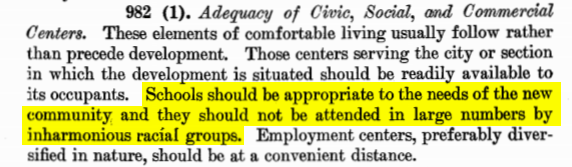

The FHA guidelines for risk assessment went into further detail regarding the risk of “racially inharmonious groups” in a neighborhood and even suggested that residing in a neighborhood where home owners’ children would attend schools with students of “far lower level of society or an incompatible racial element” increases the risk of a loan.

The maps that resulted from these guidelines were color-coded to offer a visual representation of risk of any given neighborhood. Green represented a low risk and suggested that loans could be given to residents of these areas with little caution. Red areas represented a higher risk and suggested that residents of these areas should not be granted loans or only loans with higher interest rates to offset the increased risk. Essentially, buildings and residents of these areas were written off as not worth the investment.

While there were multiple factors that were considered in assessing a location’s risk, one of the defining characteristics of these assessment forms is the inclusion of sections for noting racial makeup of an area. What this meant is that cities were divided in ways to create neighborhoods that promoted “racial harmony” – which essentially advocated the segregation of living. Predominantly white neighborhoods were viewed as lower risk while neighborhoods that consisted of foreign-born and African American residents were higher risk – this is to say that typically non-white neighborhoods, low income neighborhoods, and areas with run down buildings were drawn on these maps in red. This is where the term “redlining” comes from.

Home ownership was seen as a necessity, though, in restoring the economy and people’s societal status – so much so that even the FHA Underwriters Manual acknowledges this: “The borrower derives a measure of prestige from home ownership that often enhances his position or that of his family in the business and social worlds.” This principle continues to hold true as home ownership is a major component in building wealth – not just by the increased value of property over time, but the consideration that the payments will, one day, end leaving that money available for extra savings or investments. Being unable to obtain a home loan typically means paying rent until the end of time – that money is never yours. This has generational impact as none of that wealth or its benefits can be passed down. The neighborhoods that banks wouldn’t invest in (or couldn’t reasonably invest in as the loan wouldn’t be insured) would stagnate or deteriorate, leaving the people who resided there at a distinct disadvantage in the pursuit of the American Dream.

Lyndon B. Johnson would pass the Fair Housing Act in 1968 – 34 years after the Federal Housing Administration was created. The law prohibited the discrimination against race, religion, sex, nation of origin, family status, or disability in consideration of housing. While the idea behind it is admirable, the decades of practice preventing home ownership had already left a lasting impact that would continue for decades to come. By 1940, African Americans made up nearly 10% of the population but accounted for only 2% of the FHA loans issued by 1950. By the time the Fair Housing Act was signed in 1968, “a typical middle-class black household had $6,674 in wealth compared with $70,786 for the typical middle-class white household…. In 2016, the typical middle-class black household had $13,024 in wealth versus $149,703 for the median white household….” (Washington Post)

This is just a single, small reminder that generations of discrimination and equality aren’t easily resolved by the passage of any single law.

“If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive.” – Barack Obama, 44th President of the United States

Additional links:

- https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/

- https://www.bridgemi.com/michigan-government/michigans-segregated-past-and-present-told-9-interactive-maps

- https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2012/04/25/1934-philadelphia-redlining-map/

- https://library.osu.edu/documents/redlining-maps-ohio/area-descriptions/Akron_Area_Description.pdf

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2016/10/housing-discrimination-redlining-maps/

- https://guides.osu.edu/c.php?g=903688&p=6504406

- https://ncrc.org/holc/

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/federal-housing-administration.asp

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/federal-savings-and-loan-insurance-corporation-fslic.asp

- https://youtu.be/O5FBJyqfoLM

- https://youtu.be/LN_8KIpmZXs